The Pioneers of LGBTQ Rights: Key Figures in the 19th Century

When we think of Pride, LGBTQ equality, the gay liberation front and other key events and people from gay culture, it’s easy for us to forget that LGBTQ history is more than 50 years old.

The Pioneers of LGBTQ Rights: Key Figures in the 19th Century

When we think of Pride, LGBTQ equality, the gay liberation front and other key events and people from gay culture, it’s easy for us to forget that LGBTQ history is more than 50 years old. Many things have been said and written on these subjects, so with February being LGBTQ History month, I wanted to go further back and look at the rich history that predates these events and introduce you to a few people who have been hugely influential in the gay movement, demonstrating how the actions of a few key people started a ripple, that turned into a wave, that turned into a movement.

The Influence of Medicine on Society’s Perception of Homosexuality in the 19th Century

Homosexuality in the 19th century was, unsurprisingly, a taboo topic, often met with social stigma, legal penalties, and medical diagnoses of abnormality. In many countries, same-sex sexual acts were illegal, and those caught engaging in them could face imprisonment or forced medical treatment.

In the 19th century, medical professionals played a significant role in shaping societal attitudes towards homosexuality. At the time, homosexuality was widely considered to be a form of deviance or mental illness, and medical professionals held significant influence over public perceptions of the issue.

Medical professionals of the time used a variety of diagnoses to describe homosexuality, including “sexual inversion,” “moral insanity,” and “congenital homosexuality.” These diagnoses served to medicalise homosexuality and pathologize it as a form of mental illness. Attributing factors included, an overactive mother, an absent father, or an excess of female hormones in men. There were various treatments for homosexuality, including hypnosis, electroconvulsive therapy, castration, and even lobotomy. The most widely used method was “therapeutic” imprisonment, where individuals were forced to undergo treatment in mental institutions or prisons. Despite being considered a medical condition, homosexuality was still illegal in many countries, leading to the double stigma of being considered both a criminal and a mental patient. Medical diagnoses of homosexuality in the 19th century contributed to the widespread belief that homosexuality was unnatural and immoral, further perpetuating the discrimination and persecution of gay individuals.

Medical professionals also testified in court cases as expert witnesses. They would provide ‘expert’ testimony that was used to justify the criminalisation of homosexuality and would argue against reforms aimed at improving the rights of homosexual individuals.

Despite these negative influences, there were also some medical professionals who were more progressive and supportive of homosexuality. These individuals, including German physician and sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld, worked to promote greater understanding and acceptance of homosexuality, and advocated for the rights of homosexual individuals.

Despite the danger and discrimination, some individuals, especially in cities, formed secret gay subcultures, gathering in underground venues and using coded language to communicate. It was in the late 19th century, the term “homosexual” was introduced and became the preferred medical term for same-sex attraction.

Magnus Hirschfield (1868–1935)

Magnus Hirschfeld was a German-British physician and sexologist born on May 14, 1868, in Kolberg, Prussia (now Kolobrzeg, Poland). He is considered one of the leading pioneers in the study of homosexuality and a key figure in the early gay rights movement. Hirschfeld received a medical degree from the University of Berlin in 1892 and later became a practicing physician.

In 1897, Hirschfeld founded the Wissenschaftlich-humanitäres Komitee (Scientific-Humanitarian Committee), one of the first advocacy groups for LGBTQ rights and the first to work specifically for the decriminalisation of homosexuality. The organisation’s goals included the promotion of public education on homosexuality and the protection of gay individuals from legal and social persecution. The Scientific-Humanitarian Committee was influential in bringing attention to the issue of homosexuality and contributed to the emerging gay rights movement. They worked to abolish Paragraph 175, the German law that criminalised homosexuality.

Hirschfeld and the committee used scientific research, such as sexology studies, to argue that homosexuality was a natural variation of human sexuality and not a mental illness. The organisation also published the first magazine dedicated to LGBTQ issues and held public events to raise awareness and support for gay rights.

In 1919, Hirschfeld founded the Institute for Sexual Science in Berlin, which became one of the leading research and education centres for sexual health and rights. The institute offered counselling and support services for sexual minorities and conducted ground-breaking research on sexual orientation, gender identity, and human sexuality.

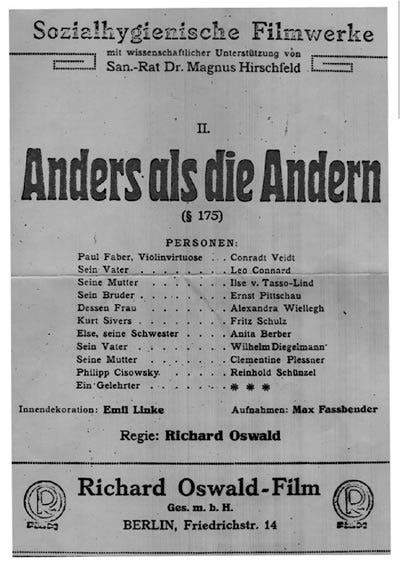

Anders als die Andern (Different from the Others)

In 1919, Hirschfield also produced “Different from the Others”. The silent film was one of the first to address homosexuality in a positive light, and it aimed to challenge the common belief at the time that homosexuality was a mental illness. The film tells the story of a successful concert violinist named Paul Körner, who is blackmailed by a former lover and ultimately driven to suicide after his sexuality is exposed.

The film was a significant event in the early history of LGBTQ rights, as it was one of the first times that homosexuality was depicted in a positive light on the screen. Hirschfeld saw the film as a way to raise awareness about the need for LGBTQ rights and to change societal attitudes towards homosexuality.

Different from the Others was well-received upon its release and was shown in several countries, including Germany, Austria, and the United States. At the premiere if the film Hirschfield addressed the audience saying;

“The matter to be put before your eyes and soul today is one of severe importance and difficulty. Difficult, because the degree of ignorance and prejudice to be disposed of is extremely high. Important, because we must free not only these people from undeserved disgrace but also the public from a judicial error that can be compared to such atrocities in history as the persecution of witches, atheists, and heretics. Besides this, the number of people who are born ‘different from the others’ is much larger than most parents care to realise. The film you are about to see for the first time today will help top terminate the lack of enlightenment, and soon the day will come when science will win a victory over human hatred and ignorance

During the Nazi regime, Hirschfeld was forced to flee Germany and went into exile in France. He died on May 14, 1935, in Nice. The Institute for Sexual Science was destroyed by the Nazis in 1933 and Hirschfeld’s extensive archives and research materials were lost. The film, Different from the Others was banned by the German government, and many copies of the film were destroyed. The ground-breaking silent film is considered lost, with only fragments of the original footage remaining.

Today, Hirschfeld is remembered as a pioneering figure in the history of gay rights and as a champion of equality and justice for sexual minorities. His legacy continues to influence modern-day activism and advocacy for LGBTQ rights, and his contributions to the understanding of human sexuality and sexual orientation are widely recognised and celebrated.

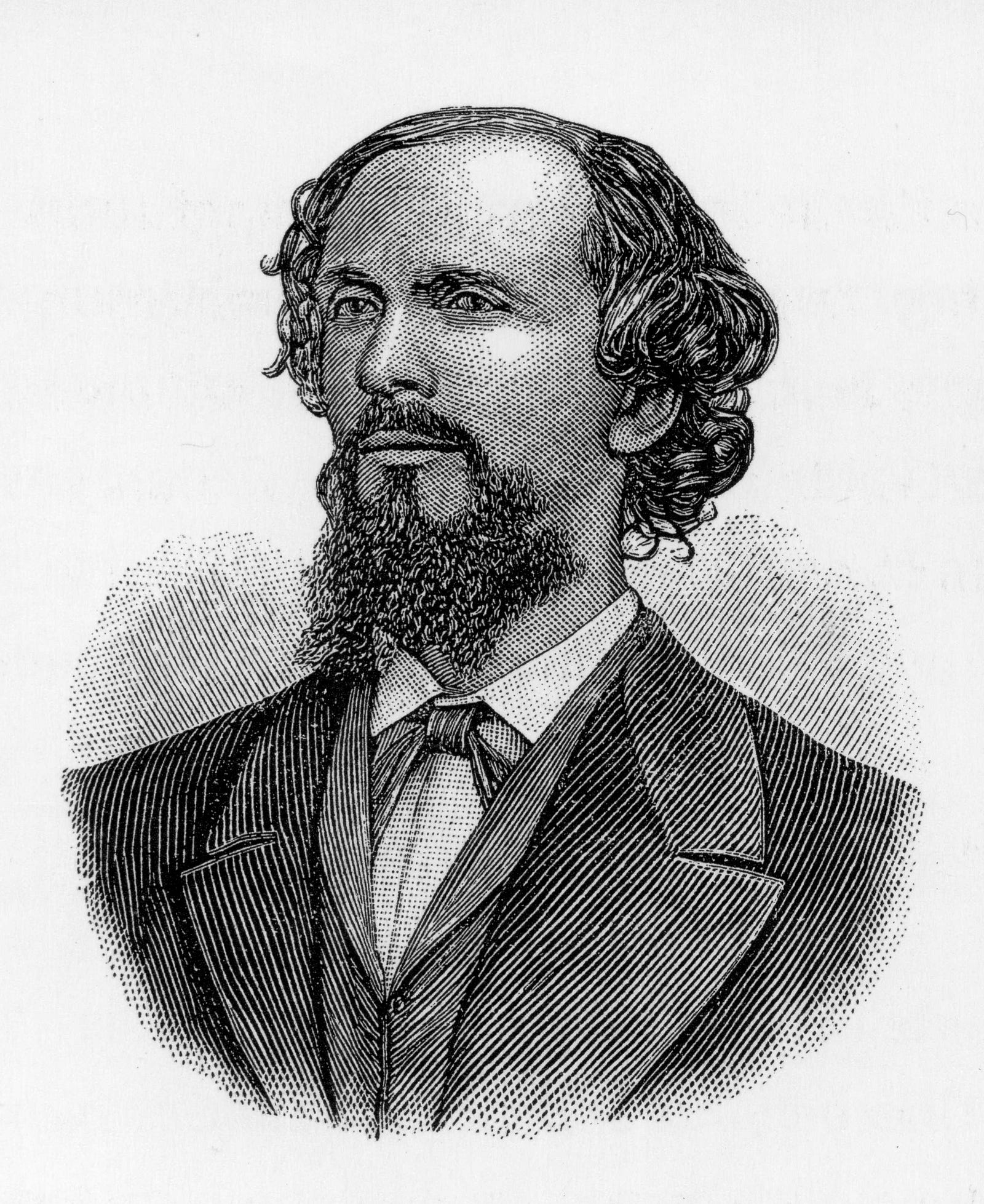

Karl Heinrich Ulrichs (1825–1895)

Karl Heinrich Ulrichs was a German writer and lawyer. He is considered one of the first activists for gay rights and is credited with having coined the term “Urning” to describe a homosexual person. This term predates ‘homosexual.’ Ulrichs grew up in a conservative, Catholic family, but he realised he was attracted to other men at a young age. Despite this, he studied law and became a government official, working in various legal positions throughout Germany. In the 1860s, Ulrichs began to publicly advocate for the rights of homosexual individuals. He wrote a series of anonymous pamphlets and essays under the pseudonym “Numa Numantius,” arguing that homosexuality was a natural variation of human sexuality and not a criminal act.

Ulrichs’ advocacy was controversial and led to him ending his career in government service. He was prosecuted for his views and was forced to flee Germany to avoid further persecution. Ulrichs continued to write and speak out for gay rights from abroad, but his efforts did not gain widespread support during his lifetime.

In 1867 Ulrichs’ attended the Association of German Jurists and spoke out, in what would be the very first time that someone had publicly spoken in defence of homosexuality. As previously mentioned, the words, ‘homosexual’ and ‘homosexuality’ didn’t even exist until 2 years later. In the book, Gay Berlin: Birthplace of a modern identity, published in 2015, the author Robert Beachy described in detail how Ulrichs, on the day after his 42nd birthday delivered the most important speech of his life. There were “Expressions of outrage, and scattered cries of ‘stop’”, writes Beachy but as Ulrichs offered to surrender to the floor, others in the audience urged him to continue.

I’ve always said, if you sit silently and don’t stand for something, you stand for nothing.

Ulrich is a personal hero of mine. For many LGBTQ people in the 21st century, it saddens me that few will know his name or the importance of what he did on that day. We talk about Stonewall, we talk about the Admiral Duncan, we talk about Section 28. Modern history is important, and I am not diluting the importance of these milestones on the timeline that is LGBTQ History, but we must never forget what happened here, at the Odeon Theatre in Munich, 155 years ago. I urge you to read the original speech online here: https://speakola.com/ideas/karl-heinrich-ulrichs-gay-rights-protest-german-council-of-jurists-1867

Origins

The word “homosexuality” was first used in the late 19th century. It was introduced by German psychologist and sexologist Karoly Maria Benkert (also known as Karl-Maria Kertbeny) in a letter he wrote in 1868 to the German government, advocating for the decriminalization of homosexuality. Prior to the introduction of the term “homosexuality,” various other words and phrases were used to describe same-sex attraction and behaviour, including “sodomy,” “uranian love,” and “pederasty.” However, these terms carried negative connotations and did not accurately describe the full range of human sexual experience and orientation. The word “homosexuality” was intended to be a more scientifically neutral term, and it quickly gained popularity and became widely used in the field of sexology and in discussions of sexual orientation. Today, the term “homosexuality” remains the most used word to describe same-sex attraction and is recognised as a sexual orientation protected by law in many countries. However, as I write this in January, 2023–71 countries still criminalise homosexuality.

It is unclear if Karl Heinrich Ulrichs and Karoly Maria Benkert knew each other personally. While both were active in advocating for the rights of homosexual individuals in the late 19th century, Ulrichs was based in Germany and Benkert was from Hungary. Additionally, Ulrichs was writing and speaking out for gay rights a few years before Benkert introduced the term “homosexuality.” Is it possible that the two activists were aware of each other’s work and influence? It’s entirely possible, but there is no evidence that they had a direct relationship. However, their combined efforts and advocacy helped to lay the foundation for the modern gay rights movement and their legacy continues to be celebrated today.

Karl Heinrich Ulrichs died in 1895, decades before homosexuality would be decriminalised in Germany and other countries. His writings would be republished by Magnus Hirschfield and would fuels his own theories, including that of a ‘third sex’ (a topic for another day).

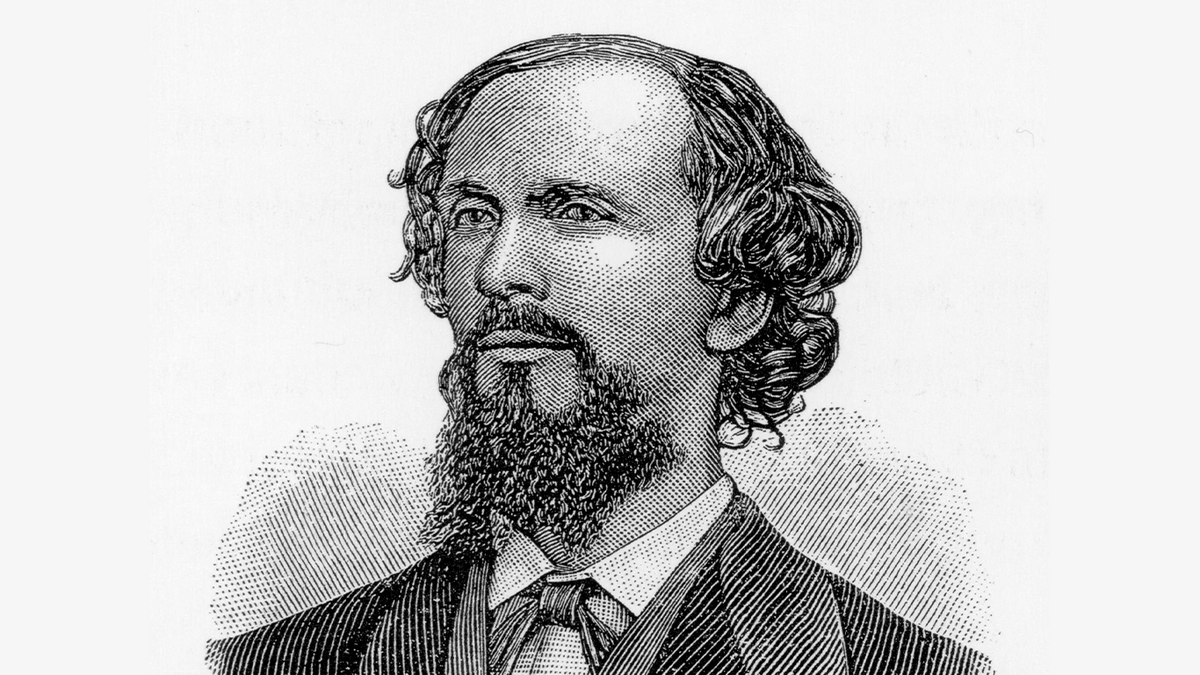

Walt Whitman (1819–1892)

In the early 19th century, the term ‘gay’ didn’t really exist. As I’ve mentioned already, homosexuality was a term wasn’t introduced until 1868. It may be possible to seek modern translations of earlier works, but as with modern translations, modern language will be used. And there is no real evidence that I could find that Walt Whitman was homosexual. Although, it was a time where same-sex attraction was widely misunderstood and punishable by law. It was commonplace for gay people to be as secretive as possible.

Walt Whitman was an American Poet, essayist, and journalist who is considered one of the most influential voices in American poetry. Born in Long Island, New York, Whitman worked as a teacher, printer, and journalist before self-publishing his first book of poetry, “Leaves of Grass,” in 1855. This collection of poems was ground-breaking in its celebration of individualism, democracy, and the natural world, and it marked a departure from traditional 19th-century poetry.

One of the most distinctive aspects of Whitman’s poetry is its frank treatment of sexuality. Many of his poems contain homoerotic themes and celebrate the beauty of male bodies. While these poems were controversial at the time, they helped to lay the groundwork for the modern gay rights movement and paved the way for future generations of LGBTQ writers and poets.

Some of his most famous LGBT-themed poems include:

- Calamus — a series of poems that celebrate same-sex love and desire, and explore themes of friendship and the beauty of nature.

- When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer — a poem that explores the limitations of science and reason and contrasts them with the emotional and spiritual aspects of life.

- Leaves of Grass — a collection of poems that includes many works that celebrate same-sex love and desire, and explore themes of individuality, freedom, and connection to nature.

- A Woman Waits for Me — a poem that explores the idea of a future relationship with a same-sex partner.

- Once I Pass’d Through a Populous City — a poem that reflects on the transitory nature of life and the importance of experiencing love and connection while one can.

Despite facing criticism for his unconventional style and themes, Whitman’s influence on American poetry is significant. He has been described as the father of modern American poetry and his work continues to be widely read and celebrated today. Many of his poems, including “O Captain! My Captain!” have become classic American poems and landmark pieces of work.

“We were familiar at once — I put my hand on his knee — we understood. He did not get out at the end of the trip — in fact went all the way back with me. I think the year of this was 1866. From that time on we were the biggest sort of friends.”

These words, recalled by Whitman are referring to Peter Doyle, a bus conductor on their meeting in 1865. Despite the challenges of living in a time when homosexuality was not widely accepted, Doyle and Whitman’s relationship was deeply meaningful to both of them, and they continued to write and spend time together until Whitman’s death in 1892. Although there is limited documentation of their relationship, the letters and journal entries that have been preserved, suggesting that their secret relationship was a romantic one.

In conclusion, the 19th century was a time of great change and evolution in the way that homosexuality was perceived and understood. The works of Walt Whitman, Karl Heinrich Ulrichs, and Magnus Hirschfeld were all significant in their own way, and helped to lay the foundation for modern LGBTQ rights movements. Whitman was a pioneering poet who celebrated same-sex love in his work and helped to challenge the prevailing cultural norms of his time. Ulrichs was a lawyer and writer who made a ground-breaking public appeal for the repeal of anti-homosexual laws in Germany, and Hirschfeld was a doctor and activist who conducted ground-breaking research into homosexuality and helped to build a political movement for LGBTQ rights. Together, these figures helped to challenge the negative stereotypes and prejudices that surrounded homosexuality in the 19th century and paved the way for future generations to fight for equality and justice.

Further Reading and References

The gay 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Gay Men and Lesbians, Past and Present, 2002.

Strangers: homosexual love in the nineteenth century, 2004

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karl_Heinrich_Ulrichs

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Walt_Whitman

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/01/obituaries/karl-heinrich-ulrichs-overlooked.html